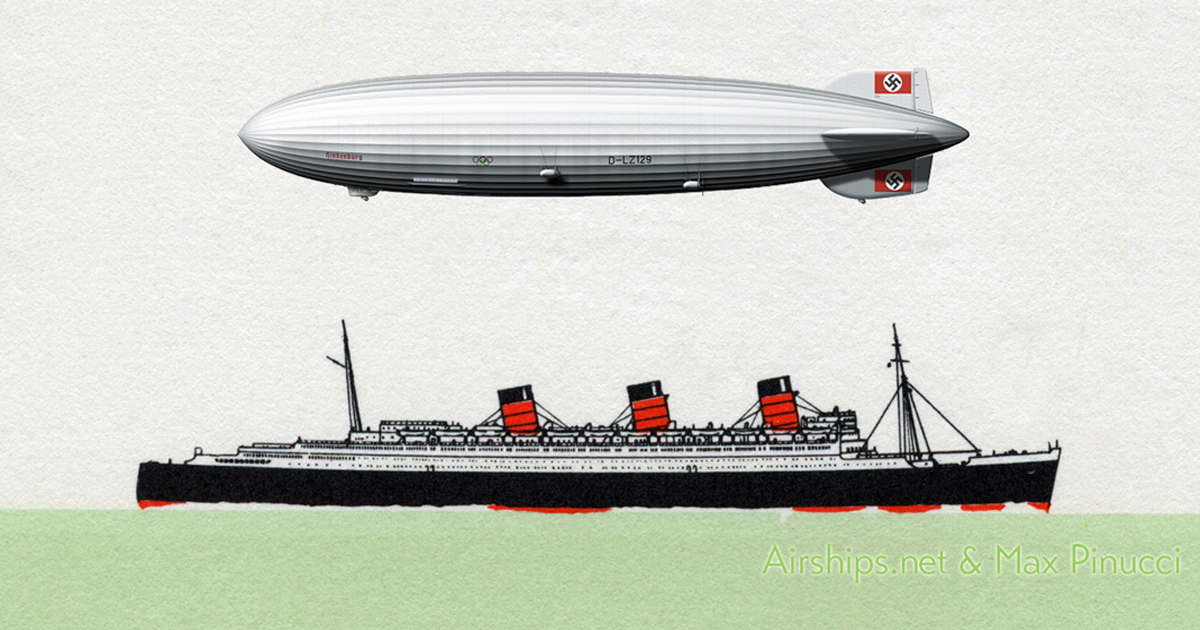

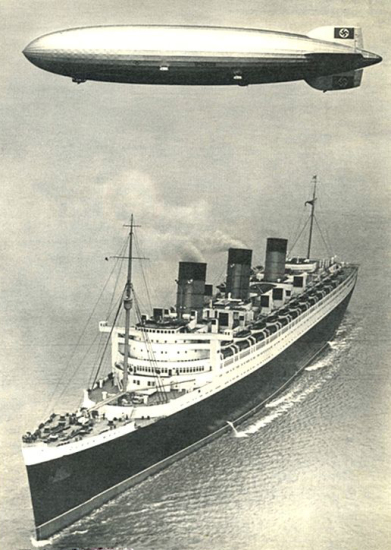

For a brief moment in history — in the year 1936 — passengers who wanted to cross the Atlantic had an astounding choice: five days of luxury on R.M.S. Queen Mary, the world’s largest ocean liner, or two days of speed on Hindenburg, the world’s fastest transatlantic passenger aircraft.

I recently sat down with maritime historian Brian Hawley to compare Cunard Line’s Queen Mary and Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei’s Hindenburg and discuss the question:

Queen Mary or Hindenburg: Which would you choose?

Speed

Queen Mary: 5 days across the Atlantic (28.5 knots | 53 km/h | 33 mph)

Hindenburg: 2 days across the Atlantic (67.5 knots | 125 km/h | 78 mph)

Queen Mary’s speed was her signature feature but Hindenburg is the clear winner; a passenger traveling round-trip between the United States and Europe on Queen Mary would spend about two weeks just crossing the ocean; a passenger traveling round-trip on Hindenburg would spent just 4-1/2 days in transit.

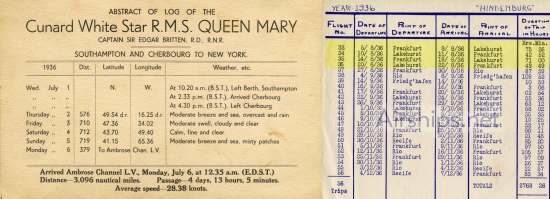

Queen Mary had a maximum speed of 32 knots and made international headlines in 1936 when she captured the Blue Riband, awarded to the fastest ocean liner on the Atlantic: When Queen Mary’s captain, Commodore Sir Edgar Britten, was asked if he would try for the speed record, he replied, “What did we build her for?” But even at a cruising speed of 28.5 knots Queen Mary took five days to carry passengers between Europe and America.

While Queen Mary’s speed was measured in days, Hindenburg’s was measured in hours. Hindenburg’s fastest eastbound crossing took just under 43 hours, and even the westbound flight — against the prevailing headwinds — averaged just 65 hours.

Schedule

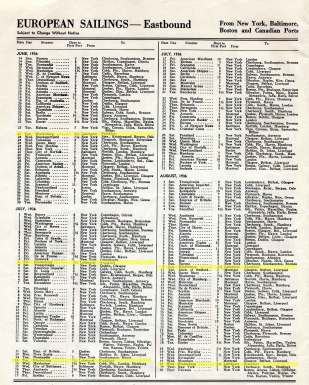

Queen Mary: Weekly service (in connection with running mates)

Hindenburg: Sporadic service (10 round-trip lyages to North America in 1936)

This may have been the biggest competitive difference between ocean liners and Hindenburg.

Queen Mary and her running mates — Berengaria and Aquitania — offered a weekly service: One of the liners left New York and Southampton every Wednesday, twelve months a year. Passengers wanting to travel or send mail across the Atlantic could count on a Cunard ship to do the job every week like clockwork.

Hindenburg was the prototype for a new service and did not have a running mate in 1936 (although several were under construction or on the drawing board). Hindenburg therefore operated a sporadic and irregular schedule, and while it was the fastest way to travel or send mail between Europe and the Americas, it was useful only if the airship’s timetable happened to coincide with a passenger’s needs.

Price

Queen Mary: $93 – $663 (per person, one way)

Hindenburg: $400 (per person, one way)

Hindenburg’s passengers paid a premium to cross the Atlantic twice as fast; while Queen Mary was one of the world’s most expensive ships, a comfortable First Class cabin on Queen Mary could still be booked for significantly less than passage on Hindenburg.

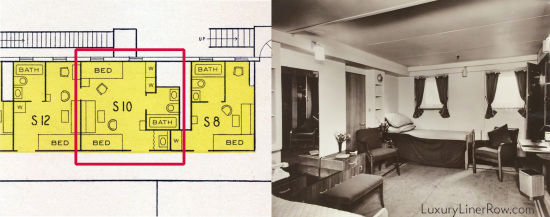

Cabin S10 on Queen Mary’s Sun Deck — a spacious First Class outside cabin with a private bathroom — was available for $295: 25% less than the $400 fare on Hindenburg.

For the same $400 price as a tiny cabin on Hindenburg, a passenger could book a truly grand suite on Queen Mary, such as M68/70 on Main Deck, which featured a bedroom, separate living room, and private bathroom.

The difference in size between similarly-priced cabins on Queen Mary and Hindenburg was astounding.

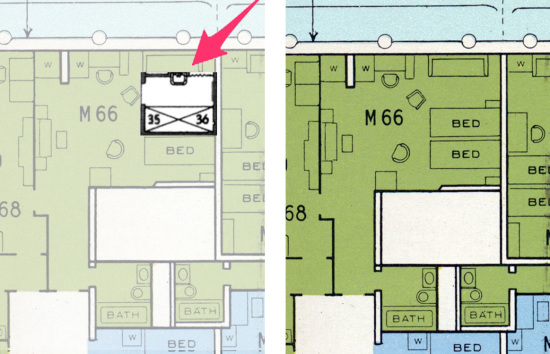

Similarly priced cabins on Queen Mary vs Hindenburg

Hindenburg cabin superimposed on similarly-priced Queen Mary cabin

And passengers who wanted Queen Mary’s speed without her First Class luxury could travel in Third Class for just $93, less that a quarter of the fare on Hindenburg.

Cabins

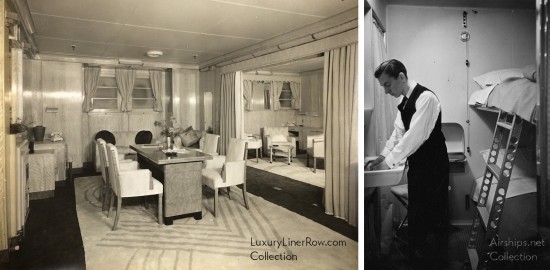

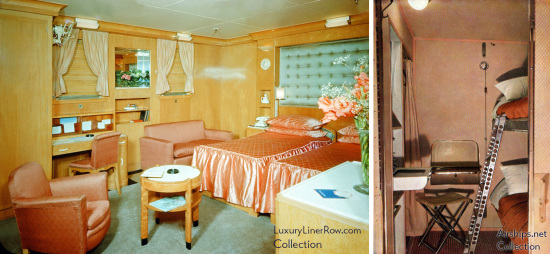

Queen Mary is the clear winner for cabin comfort: Even the ship’s humblest cabins were larger and more comfortable than the railroad-like compartments on Hindenburg.

First Class passengers on Queen Mary could choose from a variety of cabins — all of which were decorated with rare woods and comfortable furniture — ranging from inside staterooms to some of the largest suites at sea. Queen Mary’s best suites featured multiple bedrooms, bathrooms, a sitting room, a dining room, an entry vestibule, and a baggage closet that was, by itself, larger than a cabin on Hindenburg.

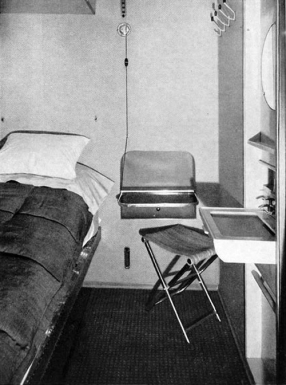

Hindenburg Cabin

Hindenburg’s cabins were tiny, and similar to the overnight sleeping compartments on railway trains of the 1930s. About 36 square feet (approximately 78″³ x 66″³), they had nothing but narrow upper and lower berths with thin mattresses, a wash basin of lightweight plastic with taps for hot and cold running water, a small fold-down desk, and a tiny “closet” covered with a curtain in which a few suits or dresses could be hung. There were no drawers or shelves and most clothes had to be kept in a suitcase stowed under the lower berth. The walls and doors were made of thin lightweight foam covered by fabric that offered no soundproofing and little privacy from neighbors, and the sleeping accommodations available in 1936 were all inside cabins, with no view outside the airship.

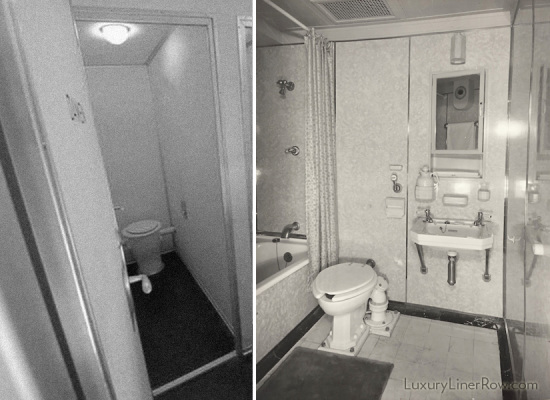

Bathrooms

Queen Mary is the clean winner here as well. Literally.

Almost all Queen Mary’s First Class cabins had a private bathroom with a tub or shower, although passengers in a few of the less expensive cabins used a bathroom down the corridor. Queen Mary offered both salt and fresh water bathing options and there was no limit about how much water a passenger could use; passengers could bathe or shower as often as desired.

Shared public toilet on Hindenburg | Private bathroom with tub and shower on Queen Mary

None of Hindenburg’s cabins had private bathroom facilities; toilets for men and women were located one deck below the cabins. Hindenburg did offer passengers a single shower, but it was more of a novelty; because water is so heavy it was in short supply on a lighter-than-air vessel, and the shower could be used for only a few minutes, and it provided a weak stream of water that was “œmore like that from a seltzer bottle” according to one passenger.

Even worse, stewards cleaned Hindenburg’s washrooms only once a day, and even in the words of the Zeppelin airline’s North American representative, F. W. von Meister: “The washrooms do not give the impression of cleanliness, particularly when 72 passengers are being carried.”

Baggage

Queen Mary passengers could bring unlimited baggage, and many people traveled with multiple suitcases and steamer trunks; the Duke and Duchess of Windsor famously travelled with 25 pieces of luggage. Items that passengers did not need during the voyage were carried in the hold free of charge.

Hindenburg passengers were limited to 20 kg (about 40 lbs) carried free aboard the airship, but an additional 100 kg (about 200 lbs) could be shipped on a German steamship such as Bremen or Europa at no extra charge.

Queen Mary Baggage Tag| Hindenburg Baggage Tag

Dress

Queen Mary passengers often changed clothes several times a day; different clothes were appropriate for morning strolls on the deck and afternoon tea in the lounge, and passengers were expected to dress for dinner in the evening; First Class passengers wore black tie every night of a crossing except the first and the last.

Travel on Hindenburg was much less formal, largely because of the very limited space for luggage. Hindenburg passengers rarely changed clothes during the day and did not dress for dinner.

Public Rooms

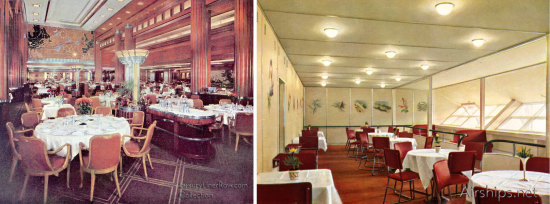

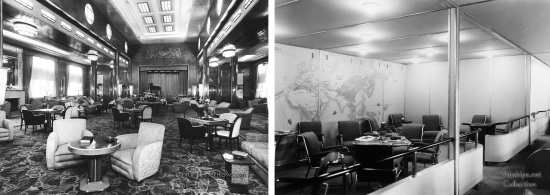

Queen Mary’s First Class passengers enjoyed thousands of feet of public space spread over eight decks. The luxurious accommodations included a dining room, lounge, library, smoking room, lecture room, music room, children’s playroom, drawing room, two writing rooms, bars, a barber shop, gymnasium, squash court, sauna, and something the lighter-than-air Hindenburg could never have provided: a swimming pool.

Queen Mary’s First Class Swimming Pool

(Colorized & courtesy Michael Davisson, facebook.com/rmsqueenmary)

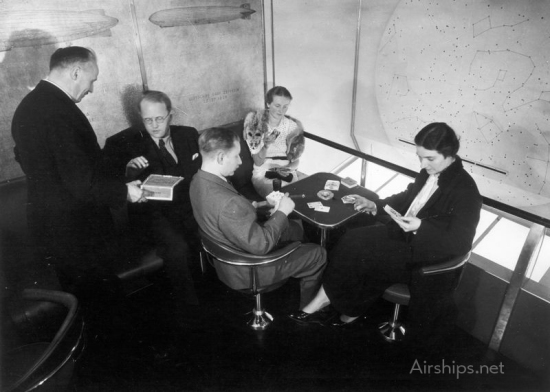

Hindenburg was itself remarkably spacious for an aircraft, and featured impressive public rooms for passengers to enjoy during their two-day journey across the Atlantic. The airship’s passenger decks included a dining room, a lounge with a specially-built aluminum piano, a writing room, a bar, a smoking room, and two promenades with large windows that opened to the scenery passing below.

Queen Mary Writing Room | Hindenburg Writing Room

Queen Mary Corridor | Hindenburg Corridor

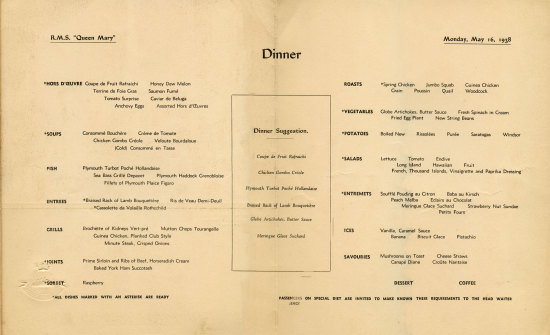

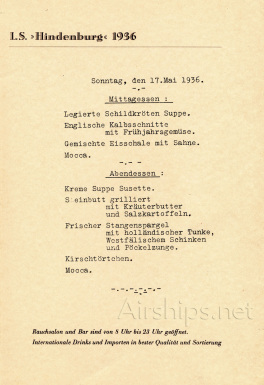

Food

Cunard was famous for “Savoir Faire, Service, and Food,” according to travel writer Temple Fielding. A dizzying array of choices was available, from an hors d’oeuvre trolley with a rotating selection to the best quality meats and seafoods. Menus changed daily and featured dozens of choices. Favorites included crown rack of lamb, pressed duck, various preparations of lobster, and tableside service including cherries jubilees, crepes suzette, and other flambé specialities. Queen Mary’s chefs were also famous for trying to accommodate requests for items that were not on the menu. Rattlesnake, anyone?

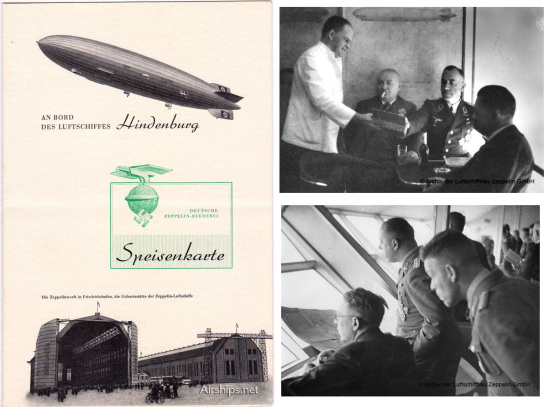

Hindenburg’s fare was less elaborate, given the ship’s small galley and severe weight restrictions; menus offered one main course which was usually a traditional German dish.

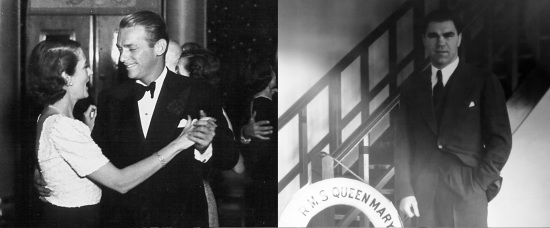

Fellow Passengers

Queen Mary carried about 800 passengers in First Class, 600 in Second Class, and 550 in Third Class.

Hindenburg carried berths for 50 passengers in 1936, increased to 72 in 1937.

For those wanting to get lost in a crowd, Queen Mary was the best way to cross; for those who were willing to mix and mingle with a small group of people in relatively tight quarters, Hindenburg was ideal.

Queen Mary’s First Class passengers also had the chance to mingle with some of the world’s most celebrated, powerful, and wealthy people. Regular passengers included movie stars like Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Clark Gable, Fred Astaire, Marlene Dietrich, and Noel Coward, along with industrialists, politicians, diplomats, aristocrats, and wealthy socialites.

Hindenburg passenger lists were more modest; the airship usually carried a mix of businessmen, a few socially prominent individuals, and ocassional members of the Nazi elite. Movie stars and real celebrities were rare, although actor Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. and boxer Max Schmeling were on the ship’s August 5, 1936 flight to North America. For the most part there was truth to the comment of fictional Hindenburg passenger Mildred Breslau who thought that ocean liners had “the best society.”

Hindenburg menu and fellow passengers

Politics

It would have been impossible for Hindenburg passengers to forget they were on a German ship during the time of National Socialism; from the giant swastikas on the tail to the portrait of Adolf Hitler in the lounge, passengers had constant reminders of the New Germany. Queen Mary was a much less political experience.

Queen Mary’s Jewish synagogue | Hindenburg’s Lounge with portrait of Adolf Hitler

Views

Crossing the Atlantic by Queen Mary was an indoor activity most of the year. The Atlantic was often grey, stormy, cold, and foggy, and there wasn’t much to see.

Hindenburg, in contrast, offered spectacular views from the large windows on the airship’s two promenades.

Hindenburg generally cruised just a few hundred feet above the ground and offered breathtaking sights over both land and water. Passengers commented on the cathedrals and castles on land and icebergs and ships on the ocean, and a highlight of North American crossings was the airship’s flight over the skyline of New York City at just a few hundred feet in the air.

Even at night the views were amazing; passenger Louis Lochner described Stuttgart in the dark: “We were simply overwhelmed by the beauty of the picture unfolded beneath us. Myriads of electric lights burning in this busy Württemberg capital gave an almost unreal picture. We could discern the main streets by their greater profusion of lights, and we realized that Stuttgart has a great white way with red and blue and green and white lights. We could almost pick out for ourselves where the movie houses must be, where the former royal palace was placed, where the airdrome was located. It was one of those sights that one cannot describe in words.”

Even the sky itself was a new and fascinating experience for passengers: “A carpet of white, fleecy clouds was spread out beneath us, looking at times like an immense stretch of glaciers, then again like a magnified collection of fluffy woolen tufts,” as Lochner wrote.

Five days staring at the ocean from the decks of Queen Mary could hardly compare.

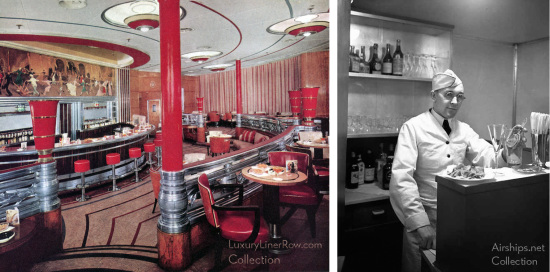

Smoking

Almost every adult smoked in the 1930s and passengers could smoke virtually anywhere on Queen Mary.

While the First Class smoking room was an especially elegant place for a man to enjoy a cigar, pipe, or cigarette, passengers were free to smoke in their cabins, in the dining room, and almost everywhere else. One thing we tend to forget when looking at photos of the ship’s elegantly-dressed passengers is that they all smelled very much like an ashtray, but people of the 1930s would have experienced the same thing anywhere else, from office buildings to railroad trains.

While the First Class smoking room was an especially elegant place for a man to enjoy a cigar, pipe, or cigarette, passengers were free to smoke in their cabins, in the dining room, and almost everywhere else. One thing we tend to forget when looking at photos of the ship’s elegantly-dressed passengers is that they all smelled very much like an ashtray, but people of the 1930s would have experienced the same thing anywhere else, from office buildings to railroad trains.

Because Hindenburg was inflated with highly-flammable hydrogen, smoking was strictly limited, and passengers were required to hand all matches and lighters to a steward before being allowed to board. But Hindenburg’s designers knew that a smoke-free airship was not likely to appeal to the nicotine-addicted travelers of the day and came up with an ingenious way to allow passengers to satisfy their cravings without destroying the airship; a pressurized smoking room entered through an airlock. The air pressure in the smoking room was kept higher than ambient pressure, so that no leaking hydrogen could enter the room, and a steward carefully monitored the door to make sure that no passenger left with a lighted cigarette, cigar, or pipe.

Hindenburg Smoking Room

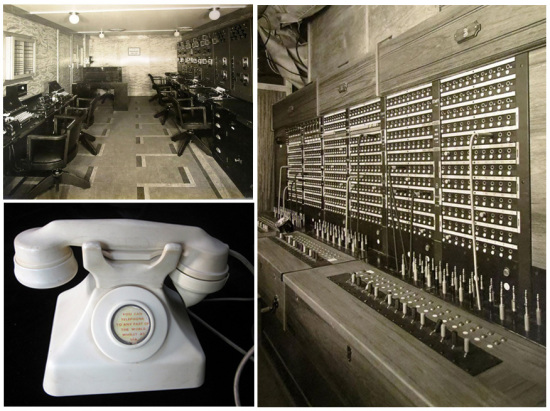

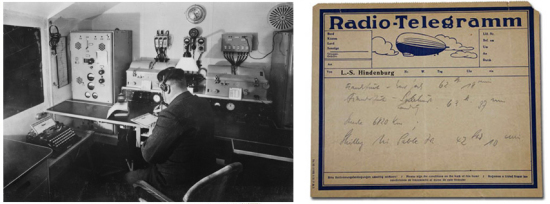

Keeping in Touch

Queen Mary’s First Class passengers could pick up the telephone in their cabin and make a phone call to any number in the world through the ship’s advanced radio room and telephone switchboard.

Being at sea for five days did not mean being out of touch, and every cabin telephone informed passengers: “You can telephone to any part of the world whilst at sea.”

Hindenburg’s passengers were limited to communicating by telegram, but of course they were only in the air for a little more than two days.

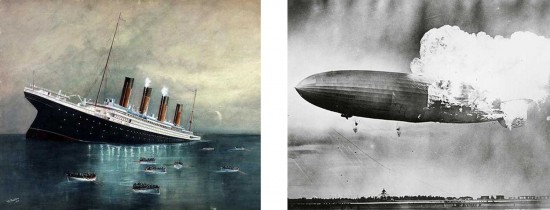

Safety

This may seem an obvious tie-breaker, but only in hindsight. By 1936 German passenger zeppelins had carried tens of thousands of passengers over millions of miles without a single passenger fatality, while the Titanic disaster, just 24 years earlier, was still fresh in people’s minds.

German airships had begun carrying passengers in 1910 and had never lost a passenger. The world’s first airline was the Zeppelin company DELAG; the world’s first flight attendant worked on a German passenger airship; and in addition to safely carrying passengers around the world in 1929, the airship Graf Zeppelin began passenger service between Germany and South America in 1932, departing Germany for Brazil almost every other Saturday. Graf Zeppelin crossed the South Atlantic 136 times and provided the first regularly-scheduled intercontinental airline service in the world, and did it without a single passenger injury.

Ocean liners could not boast a similar safety record. There were numerous passenger ship tragedies between 1910, when the first zeppelin began carrying passengers, and 1936, including: Yongala (1911; 122 deaths), Titanic (1912; 1517 deaths), Koombana (1912; 150 deaths), Volturno (1913; approx 136 deaths), Empress of Ireland (1914; 1,012 deaths), Eastland (1915; 845 deaths), Afrique (1920; 568 deaths), Principessa Mafalda (1927; 314 deaths), Vestris (1928; approx. 111 deaths), Morro Castle (1934; 137 deaths).

Even great ocean liners were not exempt from accidents; R.M.S. Olympic collided with other ships twice between 1910 and 1936, and Queen Mary herself once collided with another ship.

Hindenburg, in contrast, made 62 safe, accident-free flights before the disaster at Lakehurst in 1937. Many of the world’s most knowledgeable aviation experts had no hesitation about flying on Hindenburg, including Juan Trippe of Pan American Airways, flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker of Eastern Airlines, Jack Frye of TWA, and Eugene Vidal, Director of Aeronautics of the U.S. Department of Commerce and a close personal friend of Amelia Earhart.

While safety seems like a deciding factor in hindsight, it was not obvious at the time.

Seasickness

If anything could “break the tie” between Queen Mary and Hindenburg it was probably this.

As Mark Twain famously described seasickness, “at first you are so sick you are afraid you will die, and then you are so sick you are afraid you won’t.” Even on ships the size of Queen Mary, seasickness was a fact of life; ships of the 1930s lacked stabilizers, and despite her 80,000 tons Queen Mary was known to “roll the milk out of tea.” Seasickness was something that just had to be endured to cross the ocean: Many people dreaded crossing the Atlantic and some refused to do so for any reason.

Freedom from seasickness was Hindenburg’s secret weapon. As one passenger noted, “The real glory of Zeppelin travel”¦is its freedom from seasickness. It is the smoothest form of motion I have ever known, just a continuous floating, with no rolling, no dipping, and almost no change of levels.”

No passenger ever reported getting seasick on Hindenburg, and if airship travel had developed as planned, this might have proved an unbeatable competitive advantage.

A Choice Between Luxury and Speed. Or was it?

People often think of Queen Mary as providing her passengers with luxury. And she did. In a way.

But Queen Mary’s luxurious surroundings were only to distract passengers from an experience that was inherently time-consuming and often unpleasant; two weeks away from business and family with a dose of seasickness thrown in for good measure. Most passengers of the 1930s viewed Queen Mary simply as a way to get to their destination, and the luxurious surroundings simply made a long and uncomfortable journey a little more palatable. In fact, most first class passengers lived more luxuriously at home than on Queen Mary.

Hindenburg was not “luxurious,” either, when compared to the private homes and hotels familiar to its passengers, but the airship crossed the Atlantic in half the time of Queen Mary. If a large fleet of airships had been built as planned, offering frequent service across the Atlantic on a weekly or daily basis, the airship would have given the ocean liner a run for its money, just as the fixed-wing airliner did in the 1950s.

But still, from a modern point of view, who wouldn’t want to spend five days as a First Class passenger on Queen Mary?

So”¦ Queen Mary or Hindenburg? Which would you choose?

Please share your thoughts in the comments below.

I would like to express my sincere thanks to Brian Hawley of LuxuryLinerRow for his collaboration on this post. Brian is an ocean liner researcher, author, and collector who takes frequent crossings and cruises and often lectures about ocean liner history at sea. In addition to his deep knowledge of R.M.S. Queen Mary, Brian also has a passion for R.M.S. Olympic and published a book about that ship. Brian’s other favorite ship is Cunard’s Caronia of 1949, about which he co-authored a book with well-known maritime writer and our mutual friend Bill Miller. Working with Brian on this project was a pleasure.

An interesting article, but you missed several points for consideration. ‘Queen Mary’ was the first ship to cross the Atlantic in under four days, when she claimed the ‘Blue Riband’ from her French rival ‘Normandie’ in 1938 (a record she would hold for the next fourteen years). Whilst the ‘Hindenburg’… Read more »

I love to time-travel, when I am drifting off in bed, or onboard jet aircraft. I have Diamond Medallion Status on Delta and get a ton of perks, including almost-guaranteed upgrades, so I get snuggly front-cabin seating. I have “flown” on the Hindenburg, “taken” many transoceanic trips on White Star,… Read more »

Oh my gosh, I do the SAME thing!

My two great loves… at least we can still visit the Queen Mary and stay on her, I plan to do so on Thanksgiving for the royal brunch in the first class dining room… [sigh] what I would do to fly on an airship though. I have only this year… Read more »

http://www.searlecanada.org/volturno/volturno01.html#jan has an authoritative site on the Volturno fire. It states 134 deaths, but has a contemporary 1913 Newspaper clipping that says 136 deaths. According to the first website, this website:http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~daamen1/volturno/ is the most authoritarian Volturno fire website.

@Alan Briggs, Thanks! I will add a hyperlink in the article. Much appreciated!

The 1913 Volturno ship fire had 136 dead, and not 540 dead, as reported here.

@Alan Briggs, Thanks for the comment! I have amended the text, but could you send me an authoritative citation for my records? It would be much appreciated!

(Obviously, Wikipedia does not count. 🙂 )

It would also be interesting to compare the comfort of the Hindenburg vs the Pan Am Clipper flying boats that by 1939 were going to be the wave of the future.I think that the Hindenburg was probably much more comfortable then them as you would have much for space to… Read more »

Thanks for this article Dan. Some thoughts: 1. The comparison of cabins is not entirely fair as one reader contrasted the two ships as being totally different. The LZ129 was more comparable to a train than a ship. Trains of that era were a very effective and widely used means… Read more »

An interesting side note to the QM vs. the LZ129: The SS United States offered a solution between the airship and the ocean liner with a fast ocean liner. She averaged 30 knots but made a crossing of the Northern Atlantic in 3 days, 10 hours and 40 minutes. Compare… Read more »

SS United States was about 3-4 knots faster than Queen Mary. This was huge speed margin amongst the liners (usually Blue Riband records were only broken by fractions of a knot) but it meant less than 10 hours difference in crossing times. Blue Riband times are measured “from lighthouse to… Read more »

The queen Mary remains an icon – and I have been lucky to have spent 4 days on her – back in the 90’s – air travel has never appealed to me – but the Airship has taken a little interest to me – purely in that I marvelled on… Read more »

They had their ways, Bryan. Those people who designed the Hindenburg knew what they were doing. The Zeppelin Co. had been doing this for decades. They knew what it took to get this airship flying.

One of the passengers who flew on the Concorde was orchestral conductor Herbert von Karajan. Famed for his association with the Berlin Philharmonic, von Karajan was also an accomplished pilot and rated to fly jets. It is rumored that on that flight von Karajan was allowed to have the controls.… Read more »